New York Timesで航空問題を中心とした契約記者をしている彼女は日本に興味を持ち、ボランティアガイドについて関して私によく質問してきた。その後実際我々の紹介の記事をNew York Times用に書いてくれたり(これはまだ掲載されていない)、アメリカのラジオに出演して日本での経験を紹介してくれたこともあり、それはネット上で聞ける状態だった。

今回はやはりNYTの企画の1つ、「世界の大空港付近で週末の36時間を如何にすごすか」で、成田空港付近での過ごし方の記事を書くことになったChristineさんから私にメイルが入り、成田をガイドしてくれないかとのことだった。成田はガイドしたことがないので自信もなく、あまり乗り気がしなかったが、一緒に食事をするだけでも...と言われ出かけた。

彼女は「メルキュールホテル成田」に滞在中だったが、私の便宜を考えてくれて、京成成田駅で10時に会うということになった。

時間通りに現れた彼女はすでに前日の夜、この付近を歩き回っていて、地理については彼女の方が詳しい。予想はしていたがとても好奇心旺盛な人で、次々と質問攻め。「年間1200万人もの参詣者があるのはなぜか?」「道路の淵に並んでいる石像の動物は何を意味するのか?」「なぜウナギがここの名物なのか?」「漬物の漬けかたは?」などなど。道路沿いに並んでいる石像は狛犬だけでなく、ウサギもいて説明に困る。ウナギを生きたままさばくのを実演して見せている店もあり、頭に錐をつきたてられて、包丁でタテに2つにされてもまだ動いているウナギを見てショックを受けながらも写真を懸命に撮る。

途中、「成田観光館」という観光案内所に立ち寄る。成田の観光の新しいシンボル、ジェット機の形を模した青いツバメ(?)のぬいぐるみを成田市が熱心に作ったことを知った彼女は、成田闘争の歴史を知っていて、「空港当局と成田市が和解したシンボルなのか?」と聞き、「それは少し考えすぎでは?」と苦笑された。成田空港の近くにあって先端技術を展示する「航空科学博物館」のすぐ隣りには成田闘争の歴史を展示した博物館があるそうで、彼女はそれを見てきたという。

そうこうしているうちに気が付くと新勝寺総門の前。袈裟を着た僧侶が説明してくれる。この門は4年前の新しい建造物なのに、柱に特殊な加工が施され、古く見えるように工夫されている。仁王門の脇の厄払い用大ワラジの下に巡礼者が小さなワラジをたくさん吊るしているのを不思議がる。ベタベタ貼られた名札も好奇心の対象。

三重塔の説明をして写真を撮り、粗野なコンクリート造りの大本堂は通過して、古い釈迦堂へ。周りの木壁に彫り込まれた五百羅漢の表情が面白い。彼女は冗談に「あなたのの祖先はどれか?」と聞く。台風の影響か急に雨になる。屋根の下の階段に座って雨宿り。

間もなく晴れて、水溜りを避けながら、彼女の要望で裏の「書道美術館」に向かう。入ると正面の壁に13メートルもの高さの巨大な拓本がある。8世紀に中国山東省の山に刻まれた碑文の拓本だそうだ。玄宗皇帝の時代に彫られたもので、この寺の住職が山東省の高官と親交があり、贈られたものだそうだ。内容はよく分からないので、象形文字として説明できる漢字を拾い出して説明。ついでにカタカナ、ひらがなの作られ方の例などを示す。同じ漢字でも、筆を上げたときも筆の動きがそのまま紙の上に残る書き方と印刷文字のようにはっきり区切れている文字とでは別のものに見えてしまうようで、同じ文字だといっても納得できないようだ。しかし太くどっしりした文字と変体仮名の文字では、全く受ける感じが違うと感心する。実際私が読めない作品が多いけど、分からないのは分からないと言って、決まり文句や芭蕉の句、万葉集の歌の一部などの分かる部分だけを自分なりに解釈するしかなかった。

外に出て、ATMを探したが、銀行の機械は外国のカードを受け付けないし、日曜日なので郵便局のATMはブースに鍵がかかってダメ。あきらめて食事にする。ウナギが食べたいというが、うな重は2800円もする。うな丼で1500円のを見つけて入り、ご馳走になった。

食べながらの話で、昨夜このあたりを1人で探索したときのことで質問を受けた。成田で36時間を過ごすという話では、夜をどう過ごす考えて、バーを回ってみたらしい。カウンターがあって小さなテーブル・椅子などがある酒場で、「ここはナイトクラブか?」と聞くと妙な顔をされて、「違う」という答えが返ってくるのは何故か? という。日本ではナイトクラブというとキャバレーと一緒と考える人がいるのだろうが、Nightclubは国によって違う意味を持つようだ。また食堂に入ると中から大声でどなるように挨拶されるのは怒られているように奇異に感じるとも言う。

店を出て大通りを歩いていると、古い庶民的なダンゴ屋が目に入り、カキ氷とアイスクリームと書かれているので入ってみた。小さな店なのに170年も続いていて6代目の女主人が動かしているようだ。Christineはアイスクリームを欲しがったが、カキ氷も初めてだというので1つ注文。アメリカにも似たものがあるようだが、記事に入れたいというので、カキ氷の機械を動かしている場面や、隣でトコロテンを食べている人に頼んで写真を撮らせてもらった。壁掛けでベルが目のように正面に2つある旧型の公衆電話機なども使われていて、彼女の注意を引いた。NYTの記事の一部にする予定だと分かると女主人は飲み物をタダにしてくれた。

外に出て別れ際に彼女の著書"Deadly Departure"をもらった。ハードカバーの256ページの本で、1996年にNew Yorkのケネディ空港から飛び立ったTWA800便が離陸後、爆発墜落して230人全員が死亡した事件を航空評論家として彼女が検証したものだ。ジャンボ機が比較的近距離を飛ぶときに、経済的理由から燃料タンクのいくつかを空にして飛ぶが、その際構造上の問題もあり、タンクに残った石油が気化してちょっとしたショックで爆発することがあって、過去25年間に14回も大惨事になっていたことが判明する。しかしそれがあいまいなまま隠蔽されていたことの啓発書だった。興味深く読ませてもらったので、その読後感を送った。

<このページ上部へ移動>

THE STORY OF THE FRIEND I DID NOT KNOW

September 18, 2012 - 2:21 am by Christine Negroni

Over rice and barbequed eel, Takeo Aizawa remembered the day the bomb fell

on his hometown of Nagasaki. He was only six and sitting in his 1st grade classroom when the air

raid signal went off. All students were told to go home at once. “Some of the

older boys grabbed me by the collar,” he said, demonstrating with his hand at

the back of his neck, “and they delivered me to my house.”

Over rice and barbequed eel, Takeo Aizawa remembered the day the bomb fell

on his hometown of Nagasaki. He was only six and sitting in his 1st grade classroom when the air

raid signal went off. All students were told to go home at once. “Some of the

older boys grabbed me by the collar,” he said, demonstrating with his hand at

the back of his neck, “and they delivered me to my house.”

There, his mother took him and his three younger siblings into the garden where they sat out the attack in their homemade bomb shelter, a large hole dug into the dirt. Takeo’s father, an engineer, was working out of town. Many fearful hours passed before the family was reunited.

Before the war began, Takeo-san’s two uncles ? his mother’s brothers ? had died young but his mother defied the family odds ? escaping the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki with her husband and children ? living to the age of 95.

Recounted over lunch Takeo-san’s

story at first seemed to come out of nowhere. Moments earlier we’d been talking

about books and wondering why the eel we ordered was so expensive. But there

was a point to this conversational side street that I would come to appreciate.

Recounted over lunch Takeo-san’s

story at first seemed to come out of nowhere. Moments earlier we’d been talking

about books and wondering why the eel we ordered was so expensive. But there

was a point to this conversational side street that I would come to appreciate.

In 2010, my sister Lee and I traveled to Japan and wound up writing an article together about the Goodwill Guides, a program in which Japanese people who want to practice their English volunteer to be tour guides to non-Japanese speaking visitors. For the story, I’d interviewed an American who participated in the program and he suggested I speak Takeo Aizawa who had been his guide.

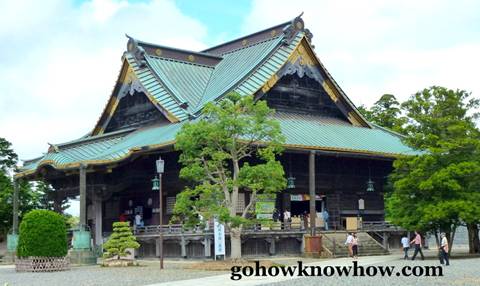

My friend Takeo Aizawa at NaritaTemple.

From that first call, Takeo-san and I hit it off. One c onversation turned into many, we emailed and we skyped. Over the past two years he has been my researcher, producer and logistical coordinator on every

story I’ve written about Japan; and there

have been quite a few. So when an assignment for Times Travel required me to visit Japan once again in September, I had one personal

priority, a face to face meeting with this friend I’d never met.

onversation turned into many, we emailed and we skyped. Over the past two years he has been my researcher, producer and logistical coordinator on every

story I’ve written about Japan; and there

have been quite a few. So when an assignment for Times Travel required me to visit Japan once again in September, I had one personal

priority, a face to face meeting with this friend I’d never met.

This past Sunday, Takeo took the train from his home in a Tokyo suburb to Narita, the town where I was staying. Together we visited Narita Temple and toured the expansive grounds. Takeo-san had never been to this complex of Buddist temples and Shinto shrines though he said his grandfather had come often to pray.

When the rain came, we ducked under the eaves of the big temple to wait out the storm.

When the skies cleared we sloshed through the puddles. We examined the sometimes unidentifiable foodstuffs for sale and we lit incense for good luck.

Finally, bushed, sweaty and really, really hungry we stopped for lunch and it was here, that I learned of Takeo-san’s experience during the war and how it became part of the circuitous path to our meeting 67 years later.

No one in Aizawa’s family was

injured when the bomb

fell on Nagasaki, but afterwards t imes were tough. No one had anything, he said and there was nothing to eat. At his house, they had only the yams that were growing in the yard. Then in 1946, through the Government

and Relief in Occupied Areas organization, the Americans started bringing in food, an estimated $1

million a day gesture Takeo-san still remembers as notably generous.

imes were tough. No one had anything, he said and there was nothing to eat. At his house, they had only the yams that were growing in the yard. Then in 1946, through the Government

and Relief in Occupied Areas organization, the Americans started bringing in food, an estimated $1

million a day gesture Takeo-san still remembers as notably generous.

“This is when I decided to learn English,” he told me, summing up his story. And that is what he did. The school boy grew up to become an English teacher and over the past 40 years he has shared the language with generations of Japanese children and happily for me, with visitors to Japan.

Today Takeo-san he is retired, but as I learned during our day together, he is still using his English to connect the past to the present, to bridge east and west and to make friends around the world.